Grave Markers

Reading a Cemetery

Chesterfield has 24 burial areas ranging from burying grounds to cemeteries. Burying grounds were used in the 1700s and the beginning of the 1800s by those who believed a body did not need to rest in sacred ground. Family plots or locations near the deceased person's home were commonly used as a final resting place. Cemeteries, planned burial grounds which included plot purchases, appeared in the early 1800s. In Chesterfield, Ware-Joslyn and Spofford (1815), West Cemetery (1830), New Boston (1832), and Friedsam (1965) became the chosen burial sites. Many families moved their loved ones into these cemeteries from the smaller burying grounds.

Gravestones and their symbols reflect the family's feeling about mortality as well as the community's values at the time of a person’s death. In New England, the gravestones and symbols evolved from the Puritan belief of preordained destiny and rejection of all graven images, (anything that depicted God or God’s creation), to the Victorian era of Greek and Egyptian statues evoking fond memories of life. Eventually, markers became more individualized, resulting in the current laissez-faire style.

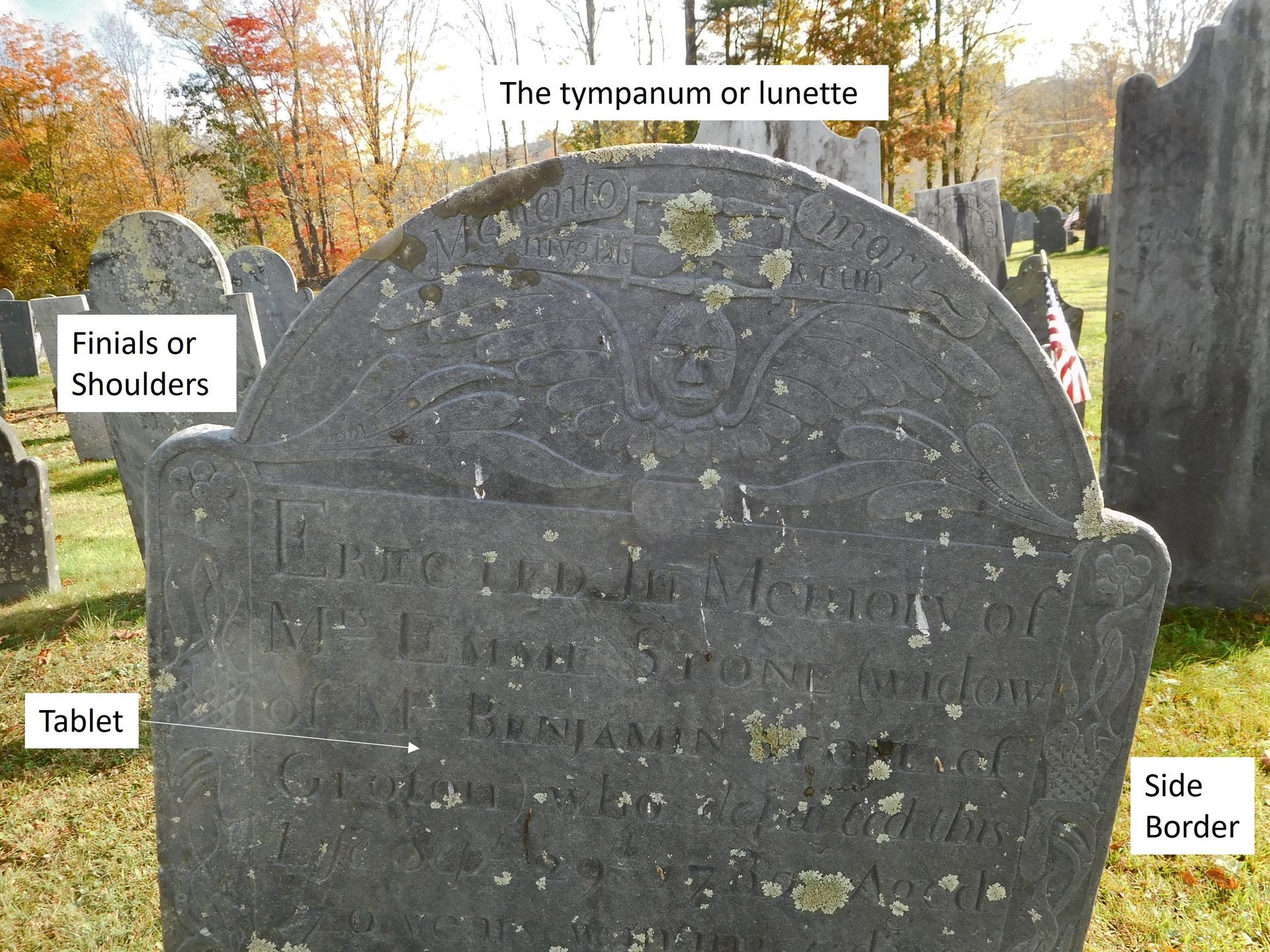

Early New England gravestones have a very specific appearance. They have four well-defined sections, looking somewhat like a bed’s headboard. The top, rounded section is the tympanum or lunette, the two smaller sides with rounded tops are finials or shoulders. The tablet contained the worded area and sometimes there are longitudinal side borders. Frequently the tympanum was the location of the death’s head or other main symbolic carvings. The finials and borders were for the gravestone’s ornamental carvings.

The tympanum of earliest stones followed the Puritan mandate of no graven images. For example, they could depict a skull (death’s head or sin) with crossbones (mortality) or a skeleton with scythe (brutality of death, grim reaper, cutting life short ). If decorative side borders were included, they contained symbols emphasizing death's inevitability. Those with epitaphs often made the point that the living can't escape the same fate as the interred. Predestination or not, the belief was that contemplation of one’s mortality was good for the soul. As time progressed the images softened to a more human-like face (soul) with wings symbolizing ascension into heaven or spiritual regeneration

As Puritanism continued to fade, the second wave of New England gravestone carvings began. Gravestone symbols were less grim and focused more on hope and individualism. They included urns (everlasting soul or return to dust), weeping willow (family love and grief), ivy and vines (friendship, fidelity, immortality), and grapes (Christ's blood). The tablets became more poetic rather than merely an announcement of death and a warning to the living that they too would die.

During the Victorian era (1837 – 1901), the markers became varied. Gravestone manufacturing improved, allowing markers to be carved from marble rather than slate, and the shape became rectangular, losing the tympanum. Victorian obsession with symbolism is reflected in the stones. For example, flowers had a language all their own, and there were books written just about them. Grave markers with floral displays became common. Cravings might include a daisy or rose bud (child, innocence, purity), a broken stem (a life cut short), or a rose (beauty of the soul, female). Religious, fraternal, and military headstones emerged. A person's occupation, and/or wealth were sometimes featured. Grave markers became layered and statues lifelike. Obelisks reflected the new Egyptian archeological discoveries that excited the era.

Late in the 19th century and continuing through the 20th, granite was used (which produced stockier stones). Engraving techniques continued to advance. Markers became more individualized reflecting the personality of the deceased. Epitaphs evolved too. They changed from doom and gloom, to thankful release from the weary world, to at times cause of death, or poetic love notes to the departed. Recent epitaphs have proven to have a more earthy tone........

“Darn those Red Sox” (Friedsam Cemetery).

As you explore any or all of Chesterfield's 24 burial areas, look at the marker variations. A marker's age can be determined by its size, shape, design, and carvings.

Rest of the Story:

Header - Center Cemetery (a.k.a Town Hall or Meetinghouse Burying Ground - Deeded to the Selectmen in 1771, it contains over 300 graves dating from 1766 - 1919.)

Rectangular Stones - The Witt family: Artemus (1823), Eunice (1842), Sally (1839), and Miss Lovisa Witt (1854) - Center Cemetery

Ornate obelisk with statues depicting areas of financial success - James J. Fiske, Jr monument carved by Larkin G. Mead (Chesterfield born) at the cost of $25,000. Fiske was a notorious gilded age robber baron whose business deals eventually caught up with him. He was murdered in 1872 at the age of 36. - Morningside Cemetery, Brattleboro.

Robertson Family Monument - Timothy N. (1913), Frances C. Swan-wife (1919), Ernest E (1859), and Helmer (1888) - Timothy N. Robertson Burying Ground (Oldest burial is 1775).