A 17th Century Ordeal

Mrs. Mary Rowlandson

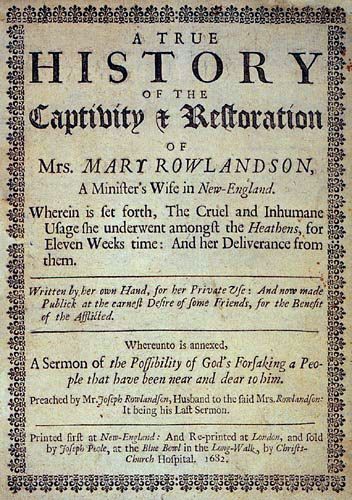

During David Mann's April program, the 1682 book by Mrs. Mary Rowlandson was noted; it was one of the first written accounts to mention the land that would become Chesterfield. "A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson", is a classic in the American captivity narrative genre and is considered by some to be the first American Best Seller. The narration emphasizes how Mary's Puritan belief (that God is the active agent who punishes and saves Christian believers) helped her to endure. However, woven throughout is a look into the Native American life and how she found herself adapting to it.

(An easily read transcript of the book is available

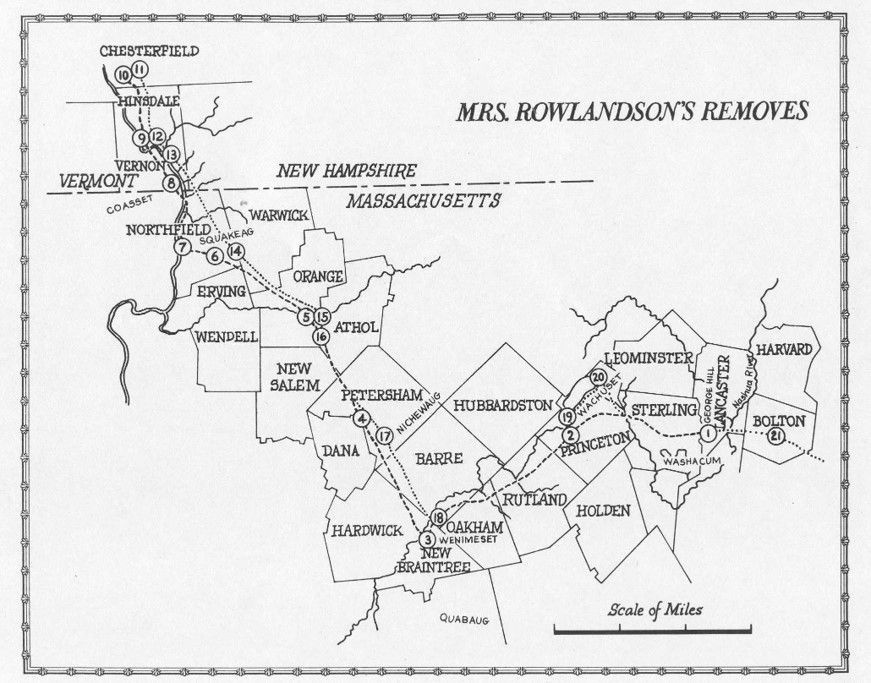

online. The book is written chronologically with each chapter numbered by the times she was moved; hence they are titled First Removal, etc., which explains the map numbers. Parts of this book are quite graphic.)

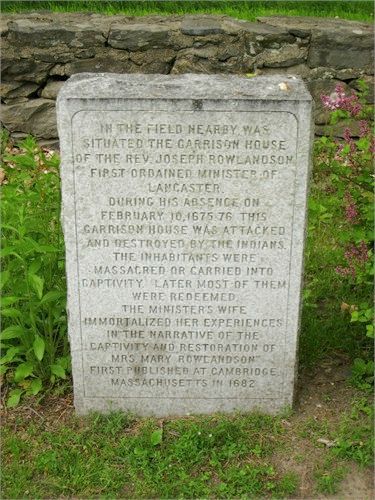

Born Mary White c1637 in Somerset, England, her parents immigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony when she was a child. They settled in Salem and then moved to the new frontier village of Lancaster. There in 1656, she married the Rev. Joseph Rowlandson, an ordained minister and Harvard graduate. Together they had four children, Mary 1657 - 1660, Joseph Jr. 1661-1713, Mary 1665 -?, and Sarah 1669 – 1676.

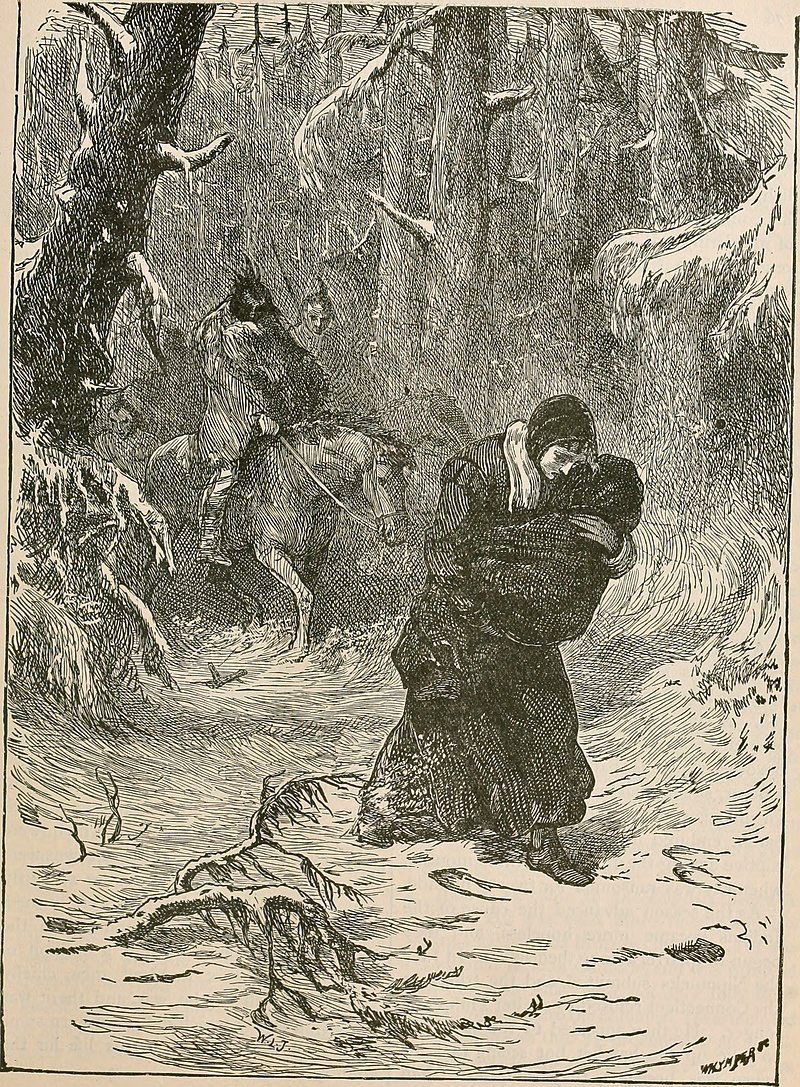

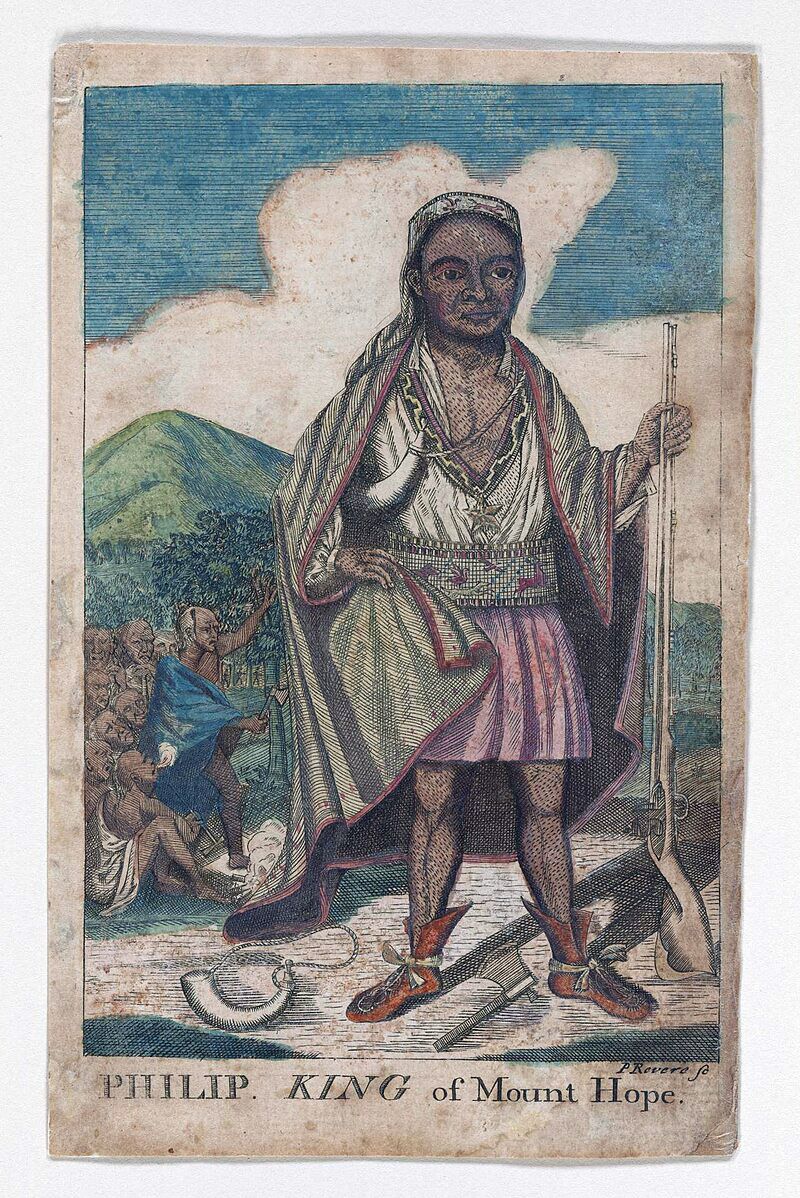

During the winter of 1675 – 76, King Philip’s War was at its height. At dawn on Feb. 10, 1676, King Philip led 400 Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and Narragansett natives against the isolated frontier community of Lancaster. During the raid, the Rowlandson garrison house was destroyed leaving 12 dead and 24 taken captive, including Mary and her three children. While fleeing the burning house, Mary and daughter Sarah were wounded.

Previously she thought she would rather die than be taken alive, but upon seeing the carnage and the horrifying way the dead were treated, she chose captivity. With gravely wounded Sarah in her arms, she traveled for four days without food or treatment for their wounds, subsisting only on water. They arrived at Weimesset, north of Quabaug (#3), where 6-year old Sarah died on the 9th day of their ordeal. Separated from her children and seeing her family massacred, only Mary's strength in God prevented her from killing herself. God rewarded her by allowing her to see her 10-year old daughter Mary, who was a captive in the same village, and hearing that her son, Joseph, was still alive.

The captives were split up and moved through the wilderness with little food and no comfort. Only the scriptures sustained her. With the English Army in pursuit, the band was increasing in size, so large that she couldn’t count the numbers. She was amazed at how effectively the squaws carried everything they owned, and the care taken with moving the old and sick. After burning their wigwams, the band crossed the Banquaug River (#6 – Miller River). She could not help but notice the “strange providence of God in preserving the heathen”. However, much to her dismay, the army’s pursuit ended at the river. Later she wrote, that it must have been God’s Will.

As her ordeal lengthened, she began to adapt. During the first week she hardly ate. The second week, it was “hard to get down their filthy trash”. By the third week, she was eating things she would never have dreamt of eating and finding them “sweet and savory to my taste”. This included half cooked horse liver and boiled old horse leg broth with entrails. But she had to be careful, for any food she gathered or received could be quickly stolen.

Because of her wound, in the beginning she could only carry her knitting work and two quarts of parched meal. She discovered her sewing skills provided her with bartering power. She knitted stockings and sewed shirts for men, women, and babies. Payment was random, but she hoped it would be food. After meeting King Philip (#8), he requested "a shirt for his boy" for which she received a shilling. After offering it to her master, she was allowed to purchase horse meat. Later, Philip requested a cap and fed her a grand meal of pancakes cooked in bear grease as payment.

Following the meeting with King Philip, she was moved further upriver. Then "over hills one of which one was so steep that I was faint to creep up upon my knees and hold by the twigs and bushes to keep myself from falling backward. My head also was so light that I usually reeled as I went; but I hope all these wearisome steps that I have taken, are but a forewarning to me of the heavenly rest"

(#11). Scholars agree that the steep hill was Mount Wantastiquet and the hills behind it were in Chesterfield. Afterward (#12), her master opted to turn south, but her mistress refused and forced her to stay with her. Weetamoo was one of her master’s three squaws. She was cruel and vain, and Mary had lost her master’s protection. For the next three weeks her life became more difficult, and due to the lack of food and often shelter, her condition started to noticeably deteriorate. During this time, she wrote that she began to doubt God’s Will.

“Sometimes I met with favor, sometimes with nothing but frowns.” "Favor" referred to being allowed to see where they buried her daughter and being invited into a stranger's wigwam to eat or sleep. She was allowed to see and speak with her son several times. And she was given a plundered bible, a much-valued treasure. "Frowns" came in the form of threats, lies, withholding food, and denying treatment for her dying daughter. She didn’t "lament, or not keep up", for she knew she would be put to death in a horrendous way. Her faith taught “to wait God’s time, that I might go home quietly and without fear.”

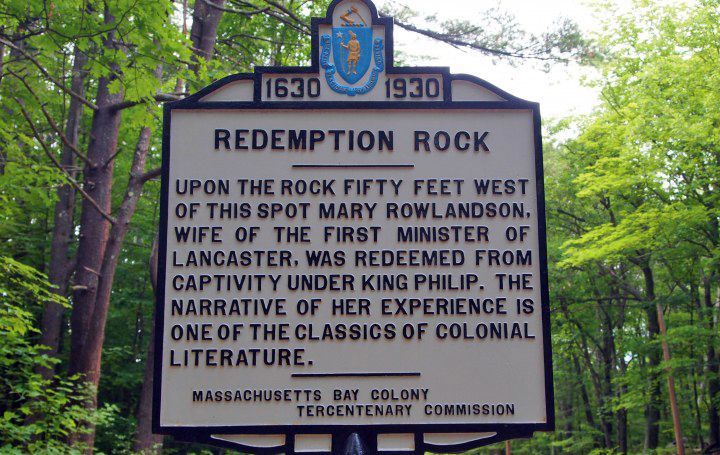

Finally, she was summoned to the Great Council (#19) and asked how much her husband, who was in Boston at the time of the raid, would pay for her. She randomly responded £ 20. Two weeks later “God hath granted me my desire”, and she was reunited with what was left of her family. She had been held for 11 weeks and 5 days and had covered about 150 miles on foot. Later, both her children were released, Joseph for £ 7, and young Mary was walked out by a squaw, "costing nothing". The destitute family was generously supported by the Boston community for a year and then moved to Wethersfield, CT where her husband became the town minister. There he died in 1678. The next year, she married Captain Samuel Talcott. Mary died in 1711 having survived Talcott by 18 years. She is buried in Wethersfield, CT. in an unknown location.