The King's Board Arrow Acts: Mast Trees for the Royal Navy

With England's forests depleted of tall trees suitable for ship’s masts,The Crown was pleased to discover an abundant source in its Northern New England colonies. The Eastern White Pine was ideal for the task. Its wood was light and strong, and the tree grew to heights of 250’, perfect as a single mast on a large sailing ship. Starting in 1691, the Royal Government restricted the cutting of white pines over 24" in diameter. Subsequent British Parliament Acts in 1711, 1722 and 1772 extended protection and eventually decrease the size to 12” diameter pine trees.

The Surveyor Deputy of the colony was in charge of overseeing these Acts and issuing the Special Royal License required to harvest a mast tree. His men were in charge of identifying all suitable trees and mark them with the King’s Broad Arrow, a series of three hatchet slashes. This designated them for Royal Navy use only. Before a settler could clear his land, the surveyor's men had to assess all white pines, marking any qualified as mast trees. Then the settler was required to purchase a royal license, enabling him to cut any remaining smaller white pine trees on his land. If a settler skirted the law, and he was found to have white pine in his cabin walls or at his lumber mill, he would be arrested and/or fined £50 - £100.

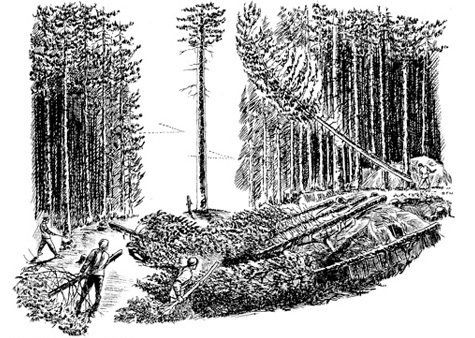

Felling and transporting a “Broad Arrow Pine” to the coast required precision and skill, plus numerous laborers. A mast pine had no value if it was split or landed in an area where it could not be retrieved. The whole process was overseen by a mast-master. Once a tree was selected, a landing area had to cleared and prepared. This process was called “bedding”. Uneven ground had to be smoothed, and rocks and stumps were covered by crisscrossing them with smaller fallen trees which would act like a cushion, absorbing the shock. Choppers, two men using axes on opposite sides of the trunk, were selected to do the dangerous job of felling it. (Saws weren’t used in the New England woods until the 1890s, over a century after the last mast pine was harvested.)

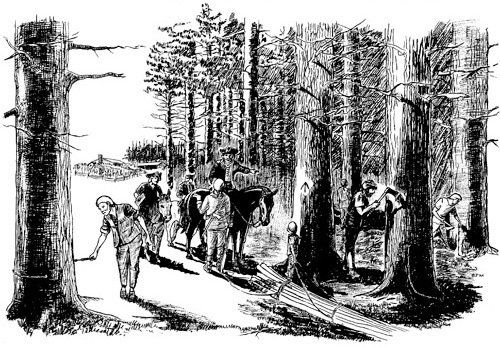

Once felled, peelers removed the bark, lower limbs, and the crown, allowing for maximum length. Then, the log was rigged onto mast wheels ranging from 9’ – 15’ high. These were pulled by teams of oxen with other teams in reserve. Two tailsmen walked behind the oxen teams to ensure no damage was done to the tree or animals. Swampers cleared and leveled a straight pathway as 120' - 250' trees didn’t corner well. These pathways lead to a substantial waterway or coastal villages. Winter was the preferred harvest time as snow covered ground made transporting the mast pine easier.

Coastal villages grew up around those hard packed mast pathways. Their town squares were often shaped to accommodate the oxen teams cornering masts through the village. Once a tree arrived at a port, it was loaded onto specialized mast ships for transport. In all, about 4500 Broad Arrow Pines were shipped from New England. However not always to England! Shipping merchants participated in a brisk foreign mast trade with or without the Crown's approval.

It is not an accident that the last mast ship arrived in England on July 31, 1775, just three plus months after the battles of Lexington and Concord. The King’s Broad Arrow Acts were one of the underlying causes fueling displeasure with the Crown. Restriction on the use of white pines had already sparked the Weare, NH Pine Tree Riot of 1772. Some historians believe that rebellion at Weare's Quimby’s Inn laid the groundwork for the 1773 Boston Tea Party, a confrontation which steamrolled into the American Revolution!

Photo Explanations:

Lead Photo: King George III Board Arrow Mark – Photo by Bill Cullina

Illustrations: Samuel F. Manning © 1977, Commissioned by ME PBS for TV Documentary “Home to the Sea” 1977

Last known Mast Wheel – Webster, NH Historical Society (9 feet tall, 1000 lbs, with axle and arch assembly weighing 950 pounds.)